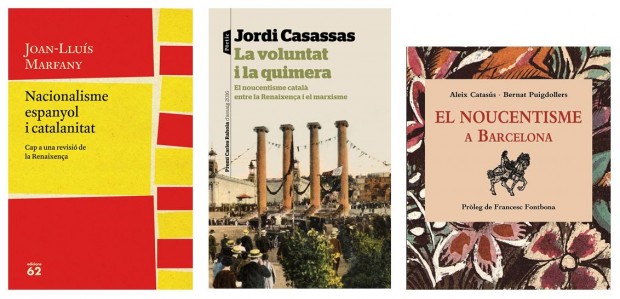

Nacionalisme espanyol i catalanitat. Cap a una revisió de la Renaixença (Spanish Nationalism and Catalanism. A new perspective on the Catalan Renaissance)

Nacionalisme espanyol i catalanitat. Cap a una revisió de la Renaixença (Spanish Nationalism and Catalanism. A new perspective on the Catalan Renaissance)

Author: Joan-Lluís Marfany

Edicions 62

950 pages

Barcelona, 2017

La voluntat i la quimera. El noucentisme català entre la Renaixença i el marxisme (Willpower and pipe dreams. The ‘Noucentisme’ movement between the Catalan Renaissance and Marxism)

Author: Jordi Casassas

Editorial Pòrtic

319 pages

Barcelona, 2017

El Noucentisme a Barcelona (‘Noucentisme’ in Barcelona)

Aleix Catasús and Bernat Puigdollers

Àmbit Serveis Editorials and Barcelona City Council

301 pages

Barcelona, 2016

For many years, Jordi Casassas has been conceptualizing the history of Catalonia by interlinking three world views: the Renaixença (the early 19th century Romantic revivalist movement), Noucentisme (the early 20th century cultural movement in Catalonia), and Marxism. His most recent work — La voluntat i la quimera (Willpower and Pipe Dreams), which won the Carles Rahola prize — centres on Noucentisme and presents it as a version of other movements that arose in southern Europe in the early 20th century (he makes comparisons with French and Italian cultural movements) in response to the inherent conflict in a democratized society for the masses. The publication of this book coincides with that of another cultural study: Joan-Lluís Marfany’s incredible new take on the myth of the Renaixença, which forces us to rethink everything we know about the first of those worldviews.

The traditional view, which tied it to the emergence of Catalanism, has always seen the Renaixença as a movement that started with Aribau’s poem La Pàtria (The Homeland). The genesis of the poem is well-known. During a stint in Madrid, on the 10th November 1832, Aribau was writing a letter to Barcelona in Spanish (the language in which he normally wrote) and he attached the poem. “For Saint Casper’s day we presented our Employer with some compositions in several languages. It befell to me to write in Catalan”. It was only in hindsight, with the intention of constructing a legitimising story, that La Pàtria was given significance comparable to the first stone of a national building. The foundations would consist of the rehabilitation of Catalan as a literary language. On top of this, a political movement would be built with identity at its centre and the Catalan language as a crucial element.

With his weighty tome, Marfany has demolished the old traditional view. He puts forward an alternative timeline (1800/1859) and fills out his work with texts that have been largely ignored by Catalan philologists. This shift of perspective changes our understanding of this period. During the course of those years, what dominated in Catalonia was the role in forging Spanish nationalism, although that did not stop our own well-to-do and liberal nationalists from unequivocally expressing a dual patriotism (to use Fradera’s term). This Spanish nationalism that was invented in Catalonia was not, of course, a single, solid structure. It evolved over time and various different forms of regionalism grew in significance. As he documents, these forms got under Barcelona’s skin, as we can see in the newly decorated façade of the City Hall, for example, or other important buildings that were designed at that time.

There are many different manifestations of this attempt to consolidate a hegemony, a worldview: by promoting a history, certain symbols, an aesthetic style. These were all ways to project an ideology and some were more successful than others. I believe that Casassas is right when he defines Noucentisme as a system, a political movement fed by intellectuals who acted as a team glued together around the politician Prat la Riba, whose aim was to regenerate a downtrodden population with the help of a systematic and modernising nationalisation process. The implementation of this worldview also left its mark on the city’s surface. It is shown and meticulously described by Aleix Catasús and Bernat Puigdollers in their book El Noucentisme a Barcelona (Noucentisme in Barcelona).

The main reason this lavishly illustrated book is so interesting is that it systematically organizes, in almost encyclopaedic fashion, a substantial part of the art produced in the city in the first three decades of the 20th century. Not all the art, because a range of different styles lived side by side, but the art that can fall under the umbrella of a loose worldview that we have agreed to call Noucentisme. Aside from the first two chapters – on ideology and the literature of this movement -, which are overly simplistic, the book is a very useful reference because it unreservedly rescues figures that have faded into the mists of time and also unifies extremely diverse forms of artistic expression: from painting to applied arts and architecture, from jewellery to garden and parks design.

The authors avoid identifying the genetic code of Noucentisme, but they give us plenty of hints. One example is their analysis of the three versions of Josep Clarà’s sculpture The Goddess. Another is their description of the schools designed by the City Council, highlighting the symbiosis between the furniture, murals and graffiti. There are, in fact, numerous examples. Why did this commendable, civilising project collapse? One of Casassas’s achievements is the way he shows how Noucentisme collided with moments of intense crisis – the Tragic Week of Barcelona, the Great War – and how this set the course it was destined to follow. In the chapter on mural painting, Catasús and Puigdollers accurately describe the role played by Torres-García in the redevelopment of the Palau de la Diputació as the seat of the Commonwealth of Catalonia: they describe his mural La Catalunya Eterna (Eternal Catalonia) (1913) as one of the iconic works of the movement and reproduce the 1917 sketch that was rejected by Puig i Cadafalch, entitled La Catalunya industrial (Industrial Catalonia). Maybe this, along with the ousting of Eugeni d’Ors from his position at the Commonwealth, provides an answer to why Noucentisme collapsed.