King Kong in the library

From the sitges festival to the 42

The Sitges International Fantastic Film Festival was founded in 1968, providing a platform for fantastic genres at a time when it seemed the only films of interest in Franco’s Spain were those of the ‘landista’ (based on comedic films starring Alfredo Landa) and folkloric genres. And like King Kong, who has become the icon of the event, the Sitges Festival has triumphed and continues to triumph over this imposed realism that claims to be “the truth”.

In this exhibition, we pay homage to the work carried out by the Sitges Festival with a focus on its relationship with literature, starting with King Kong, that take on of Beauty and the Beast which sums up the concept at the heart of it all: different kinds of narrative arts require different approaches, treatments, techniques, and so on.

This exhibition looks at approaches to the fantastic in film and literature through the Sitges Festival. Or, in other words, it follows King Kong into the library.

What makes us recognise one story in another? How much can we legitimately change when making an adaptation? What is the essence of a story? Can we approach Frankenstein without thinking of Boris Karloff? Can we read Herbert West, Reanimator without thinking about green liquids in syringes and heads on laboratory trays?

Join us on this journey through sequence shots and watch out for the blood, guts and ideas that you’ll find scattered about.

-

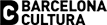

Animals like us

The transformation of humans into animals is one of the traditional themes of the fantastic genre. Becoming an animal can take away our personality and make us nothing more than a series of instincts. It can be something terrible, as Tourneur showed in his 1948 Cat People. Or it can be freedom from the oppressive layer of civilisation that constrains us, as in the 1982 remake by Paul Schrader.

But perhaps it is werewolves who are the kings of this transformation. In 1984, Neil Jordan won Best Film award at the festival for The Company of Wolves, which combines various Angela Carter stories. The spectacular on-screen transformation contrasts with the concluding idea that truly liberating change actually takes place in the mind.

-

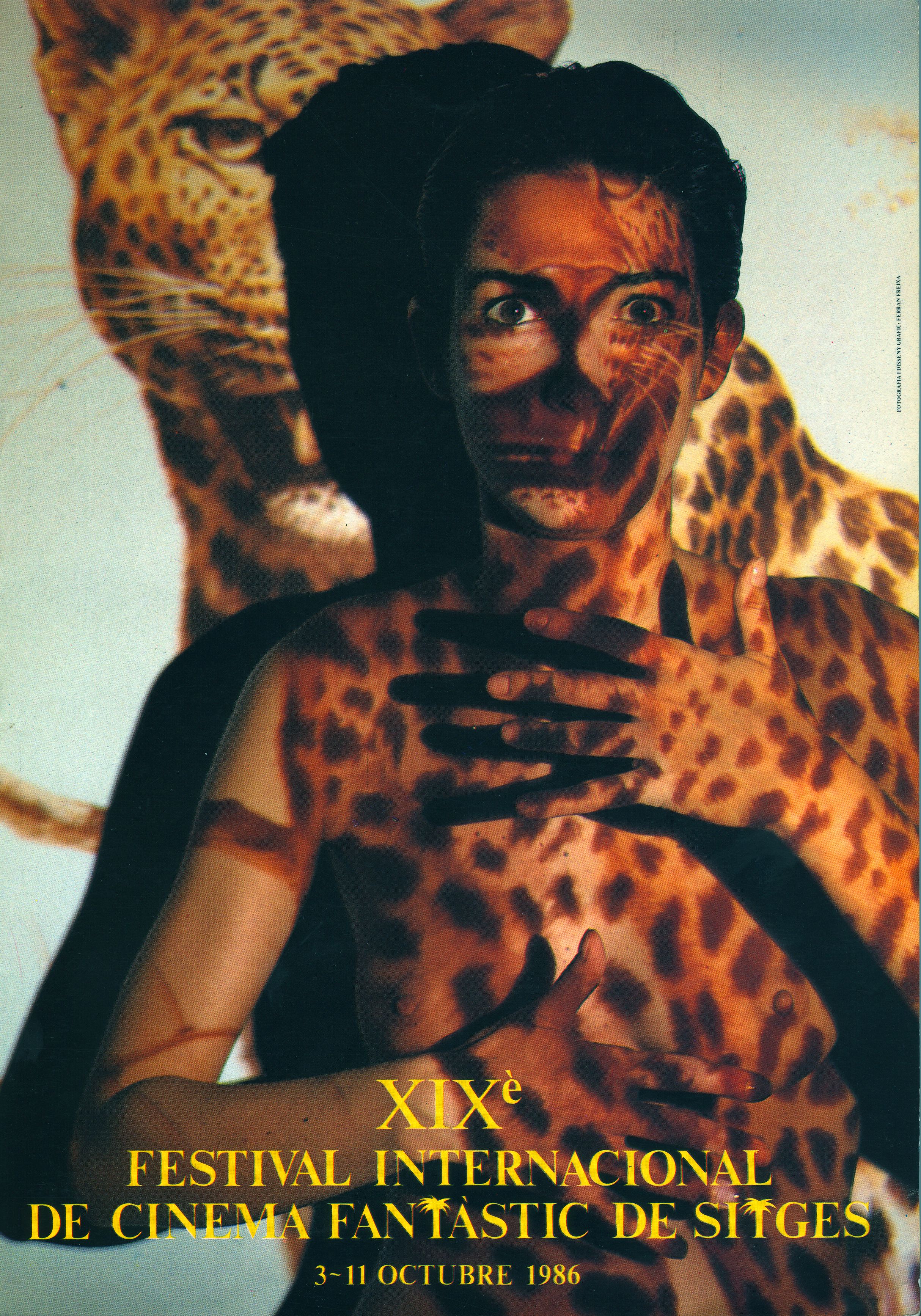

Eros and Thanatos

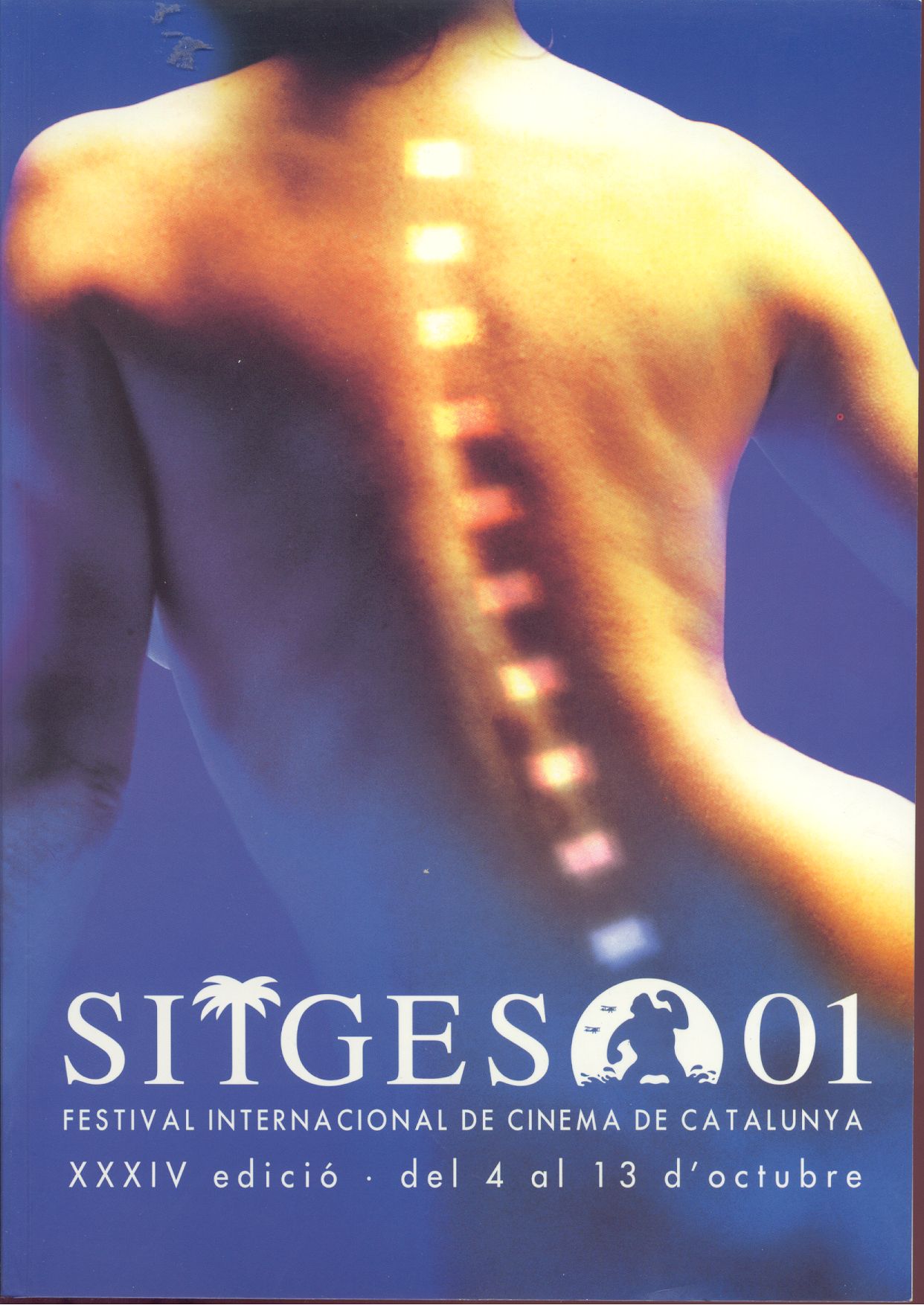

Eros and Thanatos are always intertwined in the fantastic. From the dead lovers of Poe or Hoffmann’s Olimpia in Der Sandmann, to the omnipresent sexuality of vampires, and particularly the female vampires of the 1960s and 70s, sex and death seem to go always hand in hand. So suggests the poster for the 1990 edition of the festival, which features a skull at its center.

But fantastic film is heavily steeped in this relationship: from final girls to the horny teens that meet a sticky end in any slasher movie, the women in Docteur Jekyll et les femmes and even the Cannibal Girls themselves.

-

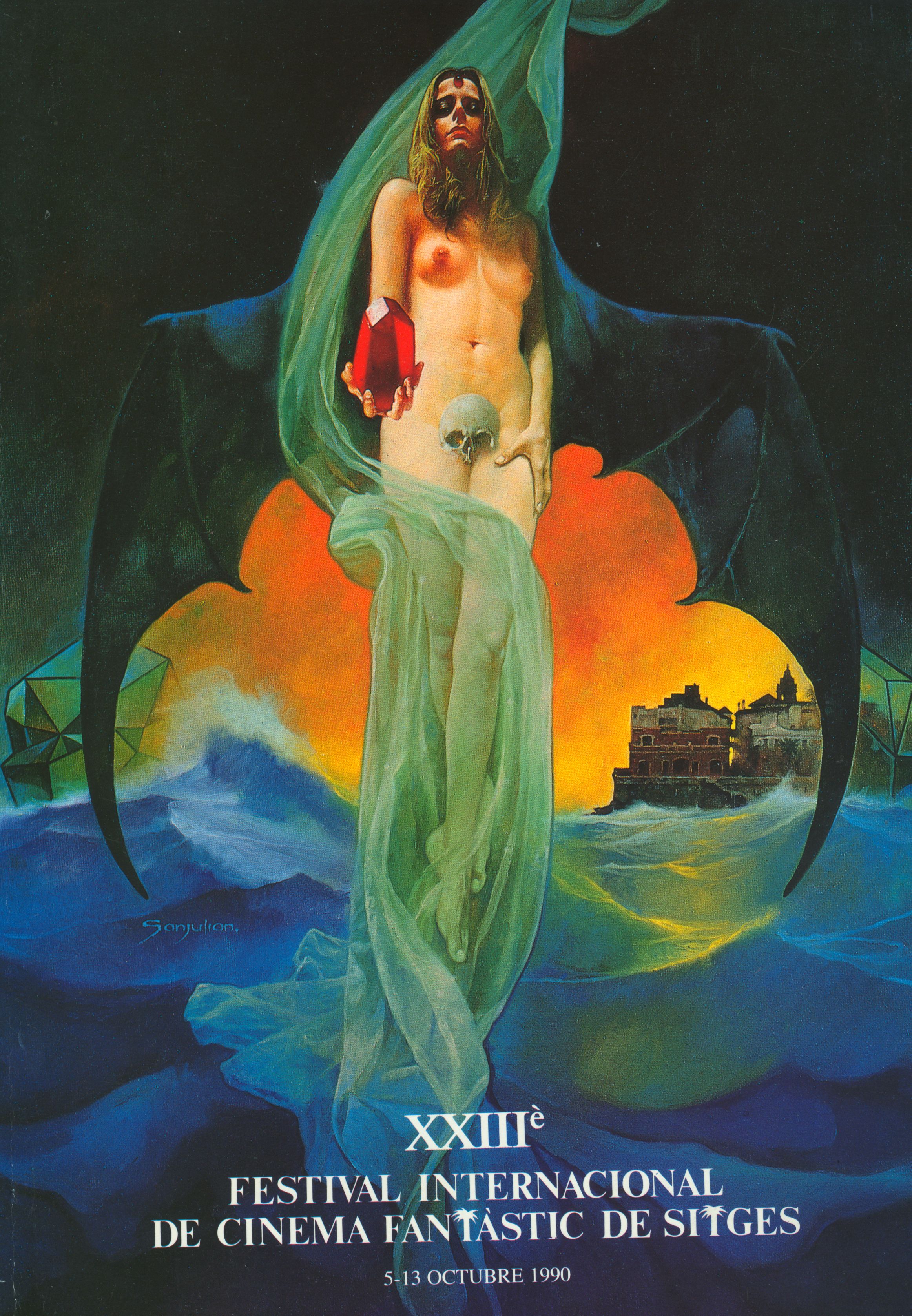

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Who are we really? The relationship between how others see us and how we see ourselves, between reality and appearance, is one of the recurring themes of the fantastic.

The design of the poster for the 1989 edition of the festival was inspired by The Picture of Dorian Gray; the following year the best film award went to Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer, a film that enters into dialogue with the story of another Henry: Jekyll.

In fact, the fantastic has always been drawn to the notion of evil in human beings, and murderers of all kinds have triumphed in Sitges time and time again: Citizen X, Vidocq, Profondo Rosso... Murderers and detectives, Jekyll and Hyde, good and evil.

-

Little animals

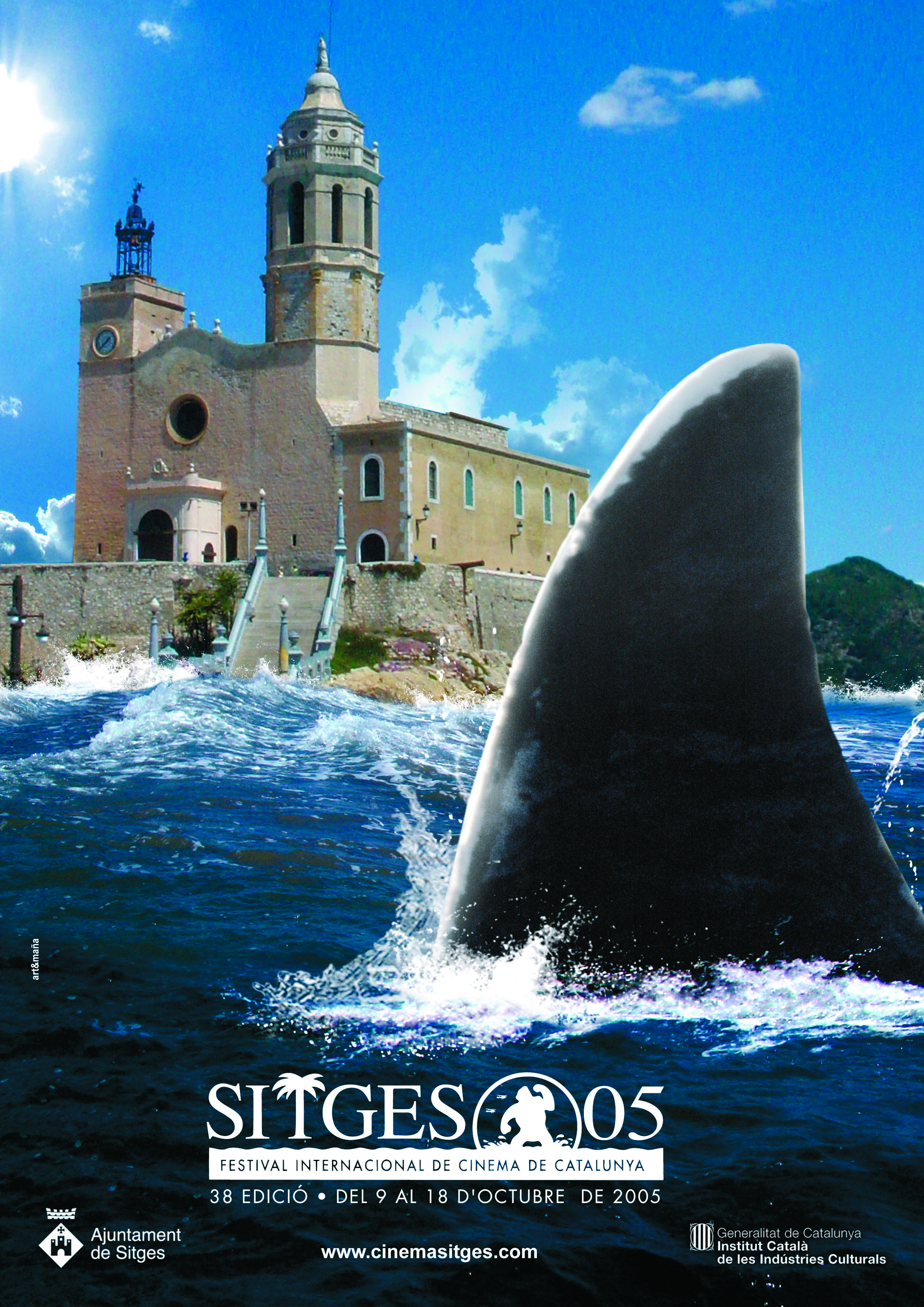

According to the cliché, the novel is always better than the film. It is perhaps for this reason that the 2005 edition poster was dedicated to Jaws, one of the best examples of a film that is leagues better than the novel it is based on.

But ravenous beasts like Spielberg’s shark, and those that are essentially its carbon copies, like Orca or Tintorera, seem to have always been there; the bats that serve Count Dracula, the cat in Pet Sematary and, above all, the ferocious wolf of fairytale fame represent this otherness that stalks us and lies in wait for us, an otherness we are unable to reason with. They represent our primordial fear of the beast that wants to eat us.

-

Doubles, twins and conjoined twins

The other is sometimes totally external, sometimes within us, but there is another otherness that fascinates the fantastic: the doppelgänger, the evil twin. From Die Elixiere des Teufels to Il visconte dimezzato, that twin who both is us and is not us fills us with fear precisely because it forces us to question our own nature.

The twins in The Shining observe us from an impossible perspective of Sitges, holding hands in a way that makes them de facto conjoined twins, because there is a link between them, that is, between us and our double, between Jekyll and Hyde, between beauty and the beast. We are inseparable.

-

More than human

While the boundary between animal and human is a running theme in the fantastic, so too is what separates us from artificial beings. Robots, cyborgs, androids and gynoids, good or evil, shine a light on all the good and all the evil of our species.

Maria, the gynoid in Metropolis which can be seen in this exhibition, is at one end of the scale. And at the other end of the scale are the cybernetic implants that implicitly make us question where the limits of being a human lie.

How many prostheses, how much that is artificial do we have to implant to no longer be considered human?

Why is it that cultural changes don’t make us question this limit but physical changes do?

-

Audiovisual literature

Film has made us think and write differently. What we used to call ‘analepsis’ is now ‘a flashback’, and intertextuality has become transmedia. At the same time, film has continually used literature as a springboard from which to create its own narratives, sufficiently close to ensure a recognisable dialogue but different enough so as not to be a simple transfer.

So, we confront the Beast with the creature from the Black Lagoon, the tale of Zatoichi is filled with colour, Bates Motel observes us with brooding eyes à la Wuthering Heights, and Frankenstein’s monster will always be Boris Karloff in our imagination.

-

Learning to read

For half a century, the Sitges Festival has been exploring the fantastic in all its forms. It was just a matter of time before it took the form of an essay, as it has for the past few years in collaboration with the publisher Hermenaute.

Through publications on different themes, we have been able to learn about lycanthropy, discover films directed by women, trace the long shadow of Caligari, or lose ourselves in the streets of cities of horror, the dark side of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, published on the centenary of the Italian author’s birth.

A text is, broadly speaking, anything that can be read, that is, that can be interpreted, from which we can extract codified information. A book and a film are therefore just two of the multiple textual possibilities out there. These essays are intertextuality and metatextuality incarnate: texts that talk about other texts, and that teach us to read them, to decipher them.

-

Awards

When we think about the Sitges Festival awards, we tend to think about the award titles: an ever growing series of categories (in the first edition there was not a single award) which now includes everything from best film, director and performance to special effects and photography.

But the awards are also the statuettes that are given to the winners, which bear witness to the relationship between film and literature that has always existed at Sitges.

Perhaps the Time Machine Award is the most obvious example of this. A representation of the machine from The Time Machine, the one we all imagine by now when we read Wells’ novel, is given in recognition of the winner’s career in the world of the fantastic.

However, it is King Kong, with his fist in the air, who is the icon par excellence of the festival. And we can see him as the beast, or as a warning against the excesses of capitalism, or as an ecological fable, or... Ultimately, King Kong calls on us to read him and interpret him. As they do in Sitges, and as Festival 42 does too. Perhaps its not a threatening fist, but rather a hand that is beckoning us to accompany him into his own fantastic library.