“Languages that are in a bell jar do not evolve”

- Culture Folder

- Interview

- Jan 22

- 17 mins

Teresa Cabré

The linguist and philologist Maria Teresa Cabré i Castellví (L’Argentera, 1947) was elected president of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans [IEC, Institute for Catalan Studies] in June 2021. She became the first woman to head the IEC, the first Catalan scientific institution, after chairing the Philology Unit in recent years, where she has promoted the approval of a new spelling and the drafting of a new grammar.

Cabré’s boasts a longstanding career in the world of linguistics. With a PhD in Romance Languages from the University of Barcelona (UB), in 1990 she was named chair of Catalan Descriptive Linguistics at the UB and, from 1994, chair of Linguistics and Terminology at Pompeu Fabra University, where she set up the Institute of Applied Linguistics.

In 1985, the Generalitat Government of Catalonia tasked Teresa Cabré with establishing and running TERMCAT, the centre for terminology in the Catalan language to promote the standardisation of terminology, in other words, to put new terminological proposals in place, necessary for the development of knowledge in the various fields of specialisation of Catalan. Member of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans (IEC) since 1989, from 1993 she ran the Lexicographical Offices and worked on the IEC’s new Dictionary of the Catalan Language, published in 1995. Winner of the Creu de Sant Jordi award, she holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Geneva.

How did being born in a small village like L’Argentera in 1947 mark you?

L’Argentera was a very small village that we thought was prettier than the neighbouring village. Back then we still believed we lived in the navel of the world. I studied at the one-room school in L’Argentera until I was nine years old, when I transferred to the school in Manresa.

Why Manresa?

The village was left without a teacher, the year they were preparing us for admission to secondary school. I should have gone to Reus. But, as they did not hire any substitutes and my parents were afraid I would miss that crucial year, an aunt and uncle from Manresa suggested I go and live with them and they would try to find a place in the school there. In Manresa I did my entire secondary education, earning my secondary school certificate.

You left home at nine years old.

With all the consequences this bears. Separating from your parents, from your siblings... Bear in mind that I wasn’t from a well-to-do family either. I saw my parents three times a year: at Christmas, at Easter, and during the summer holidays.

What did your parents do?

My father had land that he didn’t manage, and he also owned the bakery in L’Argentera. He was a baker, but also a man of great initiative, with a keen interest in the present and an outstanding organisational capacity that I may have inherited from him. He was always in pursuit of ventures that could involve the community. For example, he took the initiative to build a public membership swimming pool in L’Argentera in the early sixties, a cooperative farm in which the whole town could play a part and an inexpensive housing development.

You studied at the University of Barcelona, where you earned your PhD with a thesis entitled “Lenguajes especiales: estudio léxico-semántico de los debates parlamentarios” [Special Languages: Lexical-Semantic Study of Parliamentary Debates].

Back then I was very interested in exploring how ideologies manifested themselves through language. And because I had a liking for lexicon, I had to do it based on the study of words. The thesis was directed by Dr. Antoni Badia i Margarit, who always received my work enthusiastically, but I realised that I had to look elsewhere for the methodology. I went to the Research Centre for Political Lexicology in Paris. Back then it was at the École Normale Supérieure de Saint Claude, where I met Maurice Tournier and a lexicometry group that emerged from May 1968. So there was a concentration of progressive thinking scholars. The most right-wing was Tournier, who was a socialist. It was a tremendous hotspot of scholars.

How did your French colleagues handle the Catalan question?

Obviously we talked about Catalonia, the nation, etc., and the French found it to be far-right. At times I suffered, because in that laboratory that was so left-wing they considered me far-right, since they couldn’t accept the Catalan question, but they understood it and published a book entitled Els nacionalismes a Espanya [Nationalisms in Spain] in the seventies. They even put me on the editorial board of the magazine Mots, which was their entity.

With everything that has happened in recent years, the study could be continued...

The crux of lexicometry was its measurement of elements related to words that would reveal the discourse underlying the superficial discourse. By then it was already clear that only the parties with Catalan roots had a real concern for Catalan autonomy and that the rest, despite ardent discourses, had no interest therein. All this found its continuation in the work of Albert Morales, who has worked on the different versions of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy, and has now continued to work on the pandemic. He still applies this method based on Catalonia’s own political discourses.

You are the first woman president of the IEC in the 114 years of the institution. What does this mean?

First and foremost, it is an honour, but also an opportunity. I don’t like positions for the sake of positions, and every time I’ve accepted one, it’s because I’ve had a plan in mind. Although there was only one nomination, it was important to see the extent of the Institute members’ trust to take action. And taking action means conveying your plan to the institution and modelling it, making it work and directing it according to a plan shared with the fellow nominees.

You had widespread support.

Ninety-three per cent of votes in favour.

Your team is made up of two female vice-presidents, Marta Prevosti and Maria Coromines. However, the IEC has only 18% women.

Indeed. I sought these people out for my team, first of all, to maintain a balance within the institution. The IEC is made up of five units and there must be a relatively proportional representation of each one. There are four units represented on the team and the scientific secretary is from the unit that was not part of the management team. I sought out people with clear ideas, who had shown a capacity for work and were eager, such as the two women members, Prevosti and Coromines, and the only man, the secretary Àngel Messeguer.

You have shown that you do not like positions for the sake of positions. In the Philology Unit you have developed a new spelling and a new grammar.

Or rather I have helped to conclude, through my executive and management capacity, everything that was an open file and that would have possibly remained open forever. Based on periodisation, systematisation, rational distribution of the human resources we had... I did a lot of in-depth work to wrap up files.

In other words, during your tenure, things have been addressed that had not been touched since Pompeu Fabra.

Such as spelling. But bear in mind that, when I joined, the spelling reform project was already underway, promoted by the previous president of the Philology Unit, Isidor Marí. Following the centenary of the Spelling Rules, the decision was made to study spelling again, a matter that was never initiated, because addressing it was terrifying. As for grammar, we had gone through a really drawn-out process. Since the end of Dr. Badia’s tenure, a new project has been underway, changing model every time.

As for the Dictionary, I was already involved in the first edition of the DIEC, because I came in to help Joan Bastardes, director of the Lexicographic Offices. When he retired, at the age of seventy, I was relatively young and it was not up to me, but I had no choice but to work on it. Dr. Badia asked me to. This is how the first edition of DIEC emerged, which we had to release in four years.

Why so much haste?

Because the Generalitat Government of Catalonia made the publication of a dictionary a condition for continuing to finance the Institute. The only solution was to take the update of the Pompeu Fabra Dictionary that was being developed in the Lexicographic Offices and turn it into a new Dictionary. It was a very tough and thankless job, because it was done hurriedly and hastily. Then I started the second edition, but I went back to university. Thanks to the first edition, the second could be produced, a standardised revision of the first. If the first was done in four years, the review was done in eleven. It’s never said, and I don’t want to brag, but I have the capacity for management and execution, because otherwise the DIEC wouldn’t have managed it in four years.

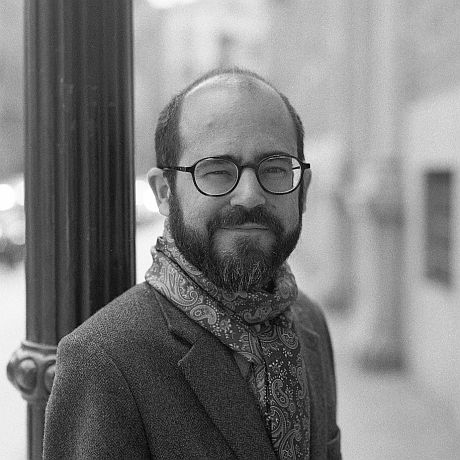

Portrait of Teresa Cabré. © Álex Losada

Portrait of Teresa Cabré. © Álex LosadaIt has announced a new pan-Catalan standard dictionary.

We announced it because the Philology Section has already started working on it. Now that we have released Spelling — and the moratorium is over and is final —Grammar has unfolded. To extract the rules of the discourse, a more simplified Grammar in digital format has been planned as well as a reference book on Basic Grammar, which is key. The most universal and usable grammar. The Dictionary is missing, because many years have passed since the second version and it is a dictionary indebted to the lexicography of the Institute, that is, Pompeu Fabra, expanded with entries from the Gran Diccionari de la Llengua Catalana published by Enciclopèdia Catalana and led by Coromines, etc. But the foundation is Fabra, and it has always been presented as an update of Fabra. We have been updating and adapting the digital Dictionary every three months, but a new Dictionary had to be produced on a different basis, and during my tenure in the Philology Section we already agreed to start working on it. We call it the Standard Dictionary and it is based on different premises.

What are these premises?

Firstly, it is not based on previous dictionaries, but on the text corpus of the Catalan language, on the language’s real discourse. There is also a change in what is considered standard. Until now, it was considered to be the lexeme present in at least two dialects. Now, however, it is considered to be what is present in more than one dialect or is a lexeme found in just one dialect, in which the word or expression enjoys prestige or is the only possible option. Thus, any speaker of a territory finds in the standard those words that they have used their entire life or are the only option in their geographical area. That’s why we talk about an inclusive standard and we call the dictionary “pan-Catalan”, because anyone who speaks from any place in the territory must be able to feel identified with it. We would like all Catalan speakers to have a single dictionary, in the same way that we have a single spelling, because the other institutions have adhered to it.

You talk about the historic agreement with the Valencian Language Academy (AVL). A few years ago, this type of agreement would have headlined newspapers, but it has gone unnoticed.

It also makes sense for it to transpire discreetly. It has been well received in the Principality of Catalonia, but there are other territories where everything that means unity of the Catalan language is contested. This agreement has been appealed at the Higher Court of Justice of Valencia, because the right considers it a betrayal of the Valencian people. But the truth is that the Valencian Government has changed, as has the vast majority of AVL members. And if AVL members believe in the unity of the language, this route has to be pursued.

Nevertheless, the most controversial matter has been the ultimate removal of a large number of diacritical accents.

This is normal, and I have taken it as a fire that will wane, but the facts will eventually prevail, because all those entities that disseminate regulations and the language model have accepted it: newspapers, publishers, schools and the government. At school it was accepted through the Department of Education, and in the media, through the agreement we made with the heads of language in the media through the Open Academy.

What has it meant to be chair of the IEC’s Philology Section in a country where language is so important and everyone has an inner philologist?

The academy needs to listen to everyone, and when a decision is made, no matter how consensual, if people do not adhere to it, it’s a failure and you have to backtrack. But this is not the case. The debate over language is positive, because it means that language concerns many people, but when you read what is written by some people who claim to be traditional diacritic zealots, you see that they make basic misspellings in their writing. There are many pre-conceptions and a certain fear of unlearning something that has had a graphic mental picture. They don’t put themselves in the shoes of someone being introduced to writing, like the child who’s starting to write and for whom you have to make things as clear as possible. And the matter of diacritics — which we remember Fabra didn’t want, like he didn’t want accents — was increasingly controversial, with no clear rules.

When the IEC is accused of being a simplifier, it is often forgotten that the great simplifier of the language was Fabra.

In an academy, decisions have to be agreed, and Fabra, as far as diacritics and accents are concerned, didn’t succeed. The rules were approved with accents and diacritics. It was strongly contended that the diacritical mark as such be eliminated, but negotiation prevailed and it was agreed that some cases be maintained that some people considered essential.

There is a two-fold concern in society: the loss of Catalan speakers and the loss of the quality of Catalan and its most authentic forms.

All languages present their own learning difficulties. I think sometimes you have to accept that languages are evolving, except for those that are inside a bell jar, which are not. However, those that you take out of the bell jar have a great deal of power to evolve at the rate of their speakers, and this is very natural. Because languages are in contact with one another, there are languages that evolve under external pressure from others. It’s about advocating for a language to evolve because it’s living, and at the same time asserting that external pressure can be legitimate as long as it does not encroach and what is being consolidated can be controlled. The moment you lose control of the consolidation, the language is encroached upon by another and the risk of being replaced is run.

Does Catalan risk ending up like that?

There must be a huge insistence, which is being reawakened, on ensuring the strength of the vehicular language in schools. Students must leave school with a good mental and linguistic structure in their own language to then acquire another language, and not have to translate. It is only with a consolidated structure in one’s own language that you can learn another.

You created TERMCAT. Is language evolving rapidly when it comes to creating new terms and accepting neologisms?

The way to create new terms in a language is to create knowledge. Especially in the specialised field, neologisms arise when you need to name things that you invent, that you create, that you discover. When there are communities that do not create but rather import knowledge, these terms are already given a name. What should these languages do to avoid being plagued by imported neologisms?

I guess the adversary must be English...

For a while it was Spanish, because English came to us through Spanish, and now we import it directly. It is not a question of not accepting any Anglicism, because, if our scientists had sufficient strength in their own language, when creating scientific discourse in Catalan, they would create and adapt borrowed words or constructions. They would adapt the borrowed term phonetically or look for a new word. There would be a spontaneous Catalan discourse, with Catalan terminology even if it stemmed from English. The problem is that we don’t have that linguistic strength and the easiest thing to do is to either do the class in English or accept all the Anglicisms. And a language that is losing communications domains is a language that is losing a part of its territory. As you lose specialised territories, a certain diglossia is created. It’s not that Catalan is unserviceable or slow, but rather that it lacks the strength and capacity to create neologisms based on its own linguistic vitality.

And what do you think of the non-binary gender debate?

It will have to be tackled at a time when it is widespread enough. Now there are militant circles or hubs, which I respect, and which do well to go all out for what they believe in. But for standard grammar to change, widespread standard use must exert pressure. A great deal more acceptance is needed for these changes to take place. That said, anyone is free to use whatever they please.

We sometimes think that the IEC is the High Court of language, and it is not its role.

The academy is not an agent of “command and control”! When the academy establishes a rule, it does not do so by royal decree, but because there are uses that exert pressure. They must be studied, examined up close, and, once they are widespread enough and adapt to the language, they are included in the standard.

One of the founding objectives of the IEC was to engage in scientific thinking and research in Catalan, precisely.

After two long centuries in which, beyond small groups with no visibility, there was no formal discourse in Catalan or science in Catalan, the creation of the IEC met the need for a structure dedicated to studying, collecting and describing Catalan heritage in all sectors, whether legal, archaeological, literary or scientific.

Has the IEC been closed in on itself?

Large and longstanding institutions find it difficult to adapt to change in an expeditious manner. For instance, communication has been somewhat abandoned. It was more important for members to be able to get involved in research than to disseminate it, and perhaps much of the IEC’s work has not been well externalised or publicised. Often, if things are done very well but they are stowed away in the drawer, they have no impact.

Is this IEC tradition a burden or a privilege?

This tradition is both. As a burden, there will always be people who will cling onto the legacy, and if taken as an anchor, it prevents us from moving forward. But the institution’s longstanding nature protects it, because it has consolidated a series of things that makes sure we cannot backtrack and the institution does not disappear. That’s why I think it’s good that mandates are established for four years with the possibility of a four-year extension, because when a person starts they have new ideas and that is fundamental. Otherwise, the burden of history would drag you down.

The IEC was founded by Enric Prat de la Riba from Barcelona Provincial Council. What relationship do they have with public institutions?

I will fight for the IEC to become a reference point for public institutions as well for the sake of our work. Not arbitrarily, not just because we were founded by the political establishment. I do not envisage that public authorities support the IEC in a unique manner, but that the IEC should be equipped with the necessary resources to do what it believes is efficient to do and that will help the country. It’s about believing in dreams, which allow you to go a bit further. If you don’t believe in a more far-off horizon, it’s hard for you to do great things. And if you only believe in the present and don’t look to the future, you are just muddling through.

What legacy would you like to bequeath from here in eight years’ time?

Behind closed doors, I would like the IEC to be organised and have a change of culture about how it works, through specific projects, characterised by transparency and accountability, and so forth. Outwardly, I would like the Institute to exert an impact through its authoritative and scientific opinion; we concentrate a body of experts from all over the Catalan language and culture territory in all scientific subjects. The final thing I would like is for the Philology Section to recover the energy and time needed to undertake scientific projects like other sections that are not responsible for establishing the standard language.

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments