Portraying the world before changing it

- In transit

- Jan 22

- 9 mins

Patrick Radden Keefe believes in the journalism that tirelessly seeks the truth to dig deeper and make information the first step in transforming the world. In a conversation with Mònica Terribas at the CCCB, he shared how he understands and practises investigative journalism in this respect. We can read his work in The New Yorker and his latest books, Empire of Pain and Say Nothing.

In 2021, Empire of Pain (PanMacmillan, 2021), the latest bestseller by Patrick Radden Keefe, was released. He is a journalist for The New Yorker and an author of other non-fiction books, which include Chatter (Random House, 2006), The Snakehead (Anchor, 2009) and Say Nothing (William Collins, 2020), winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Orwell Prize. Radden Keefe has published articles in The New York Times Magazine, Slate and The New York Review of Books.

Following a midday press conference and a slew of interviews, on the afternoon of 22 September 2021, the acclaimed writer Patrick Radden Keefe gave an interview at the CCCB, conducted by Mònica Terribas, to share experiences and exchange views about the journalistic profession. The long line of curious attendees forming in the CCCB’s courtyard, the Pati de les Dones pointed to the success of an event that would take place in the main hall.

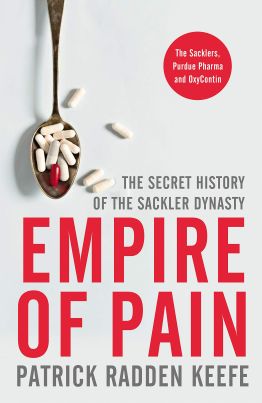

Radden Keefe had to cancel his last visit to Barcelona on account of the pandemic, so this time he came on a two-fold mission: to call to mind the multi-award winning book Say Nothing (William Collins, 2020), a collection of stories that give an account of the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the IRA’s murders, as well as to present Empire of Pain (PanMacmillan, 2021), his latest non-fiction book. The latter portrays the philanthropic Sackler family as the culprits behind a a devastating social crisis in the United States as a result of OxyContin, the addictive opioid marketed by Purdue Pharma, the clan’s main enterprise. Patrick Radden Keefe began penning this book in 2017 and remembers his surprise during the lockdown, when writing from his bed, most people answered his calls and were eager to talk at length because of the solitary monotony of those days.

The “write around” research method

The American journalist is affable, cheerful and charismatic when he explains his methods for choosing a research topic. Radden Keefe emphasises how fortunate he is to work at The New Yorker, where he has been writing for fifteen years and where he can freely choose the story that will be the material for an article or book like those he presented at the CCCB last autumn.

Unlike the convenience preferred by many of his colleagues, he is up against an obstacle that stops him from directly accessing a first-hand source, the person directly involved. This is what he calls “write around”, a form of writing that is forced to revolve around the person at the heart of the story. This process stimulates the writer because it forces them to be creative, to speculate and to explore many areas. This circumlocution is related to the fact that Radden Keefe broaches the most topical issues, so very often this kind of critical intervention may bear immediate consequences, very awkward for people who are impervious to the truth. For this reason, it must be documented with an arsenal of archives; but, above all, interviews must be conducted with possible contacts and those who may act as a secret door to the most valuable and confidential information. Two examples will help elucidate this better.

His latest non-fiction book portrays the powerful Sackler family as the culprits behind a devastating social crisis in the United States as a result of the addictive opioid OxyContin.

Patrick Radden Keefe joked that the books Say Nothing and Empire of Pain could actually be titled as such because both former IRA commander Gerry Adams, in the first book, and all Sackler family members, in the second book, flatly refused to cooperate or provide information to resolve the conflicts raised. The case of Adams is special, as he has signed numerous memoirs and gives interviews from time to time, but Radden Keefe emphasises that he is “clever”, meticulously monitoring everything he utters, and only making public what is of interest to him. In the other case, Radden Keefe has run into many closed doors each time he tries to get in touch with the Sacklers, but has found alternative paths in the housekeepers, the company doormen and those secondary characters that, from the sidelines, could hold the key to unearthing and discovering the clan’s involvement in the multiple opiate overdoses that American society has endured since Purdue launched its star product, OxyContin, in 1996.

Thus, at first the journalist only sees the tip of the iceberg, a secret that promises a truly novel-like intrigue; and once they begin to dig into a terrain they cannot stop digging deeper until they get to the bone marrow. Thus we find the parallelism between Radden Keefe’s two books: both are based on denial, the leading characters deny access to the truth because, ultimately, they fraudulently deny their involvement in a web of injustice.

Private details

It may come as a surprise that the author has peppered his books with so many private details of some people, at first sight, unnecessary. Radden Keefe points out that revealing private information is not motivated by sheer sensationalism. These tiny biographical anecdotes make up the key moment in which the journalist becomes a writer. The journalist points out that, after reading a book, it is sometimes enough to remember the impact of a single sentence, a single tiny detail that has been lodged in memory, because, like a trigger, it triggers the entire memory of a character, or of the imagined sum of a book. Thus, in order to move from the journalistic to the novelistic stage, the journalist must know how to portray “three-dimensional” characters, choosing their most crucial features, so that the novel acquires an effect that is sufficiently plausible to be accessible to the reader.

Portrait of Patrick Radden Keefe. © Mariona Gil Sala

Portrait of Patrick Radden Keefe. © Mariona Gil SalaRadden Keefe’s intention has been to write a book that upholds the rigorous nature of an academic essay, but with a depth that is accessible to a non-specialist audience.

Some people are easier to novelise: whereas Jean McConville, as a result of her murder by the IRA, can be read more as a symbol than as a character, Arthur Sackler, the eldest son of the brothers running Purdue Pharma is an extraordinary character, in his opinion. Radden Keefe’s intention has been to write a book that upholds the rigorous nature of an academic essay, but with a depth that is accessible to a non-specialist audience.

With a view to achieving plausibility, Radden Keefe recalls a simple but effective piece of advice for Hollywood screenwriters: “The villain in the movie never sees themselves as the villain”. Everyone can believe they are the hero of their story, and it can be a defence mechanism for the Sacklers not to have to bear a guilt that until recently they had not assumed in the courts. This perspective must be borne in mind when we interpret the grandiloquence with which the Sacklers have built an account of themselves as rich benefactors of cultural heritage with their philanthropic donations and their narcissistic taste for naming museum sections thanks to a spotless reputation.

It took the endeavour of Radden Keefe’s journalistic fiction to make public the private interests of a company that has deliberately sown addiction in American society over the past two decades. Radden Keefe and other precedents, such as Barry Meier, are committed to thorough research to discredit a thriving multi-billion-dollar industry that has claimed thousands of lives in the United States, to increasingly extricate the prestige from the Sacklers’ legacy (for instance, the New York Met is currently debating whether to rename the museum’s Sackler wing), in order to tinge the name with the shameful colours of infamy and mercenary ambition.

A message in a bottle

One of the key issues is whether something has changed in society since the author’s publications. When asked this question, after taking a moment of silence to reflect, carefully, Radden Keefe argues that one should work to portray the world, because this is the first step before changing it, although he acknowledges that he would be guilty of optimistic naivety if he thought he could transform it. He goes on to cite the example of Elizabeth Kolbert. When, in an interview, the interviewer questioned whether she could stop climate change, she suggested thinking about it in these terms: journalistic involvement should be like writing a message stored in a bottle. The crux of the matter is to show future generations that, beyond whether we were able to remedy it, we were at least aware of the existence of this conflict. Naturally, journalism, which tirelessly pursues the truth, should not be limited to a portrayal of the world that fits in with the hegemonic and comforting point of view of power or that responds to commercial interests.

Portrait of Patrick Radden Keefe. © Mariona Gil Sala

Portrait of Patrick Radden Keefe. © Mariona Gil SalaHis message has vexed business positions that have so far made a pretty penny from suffering to build an empire of pain.

By way of his latest book, Radden Keefe believes that his message has undoubtedly vexed business positions that have so far made a pretty penny from suffering to build an empire of pain. Otherwise, he would not have received threats or even constant stalking during the lockdown, as he says at the end of the book. Nevertheless, the journalist insists that it is not enough to impose economic sanctions on the company through the trial taking place while Purdue Pharma is suspiciously declared bankrupt, due to some “odd” coincidence. It is paradoxical that a family that enjoys naming museum collections so much has so scrupulously hidden itself from their business ventures, from a strategic and cruel backroom. Radden Keefe recalls that no justice will be done as long as the company is blamed and not the people running it; he compares it to trying to hold an interchangeable, impersonal car accountable, and not its drivers. For the Sacklers, this is just a “speeding ticket”, a carte blanche so they can continue to commit crimes under other forms of camouflage.

In short, investigative journalism must be like “a chewing gum stuck to the sole of a shoe” for the powers that be. This is how Radden Keefe recalled how an anonymous person involved with Purdue had defined his book. And this is how Radden Keefe wished to bid farewell to the Barcelona public, once again reiterating his enthusiasm for the profession and, addressing new journalists, he advised patience, perseverance and effort. An example of his fast-paced, restless and committed pace lies in his current preparation of a collection of short stories for next year, previously published in The New Yorker, such as one that bizarrely links the CIA to the origin of the most famous Scorpions song, Wind of Change.

Recommended publications

Empire of PainPan Macmillan, 2021

Empire of PainPan Macmillan, 2021 Say nothingDoubleday, 2020

Say nothingDoubleday, 2020

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments