The discourse trap that drives young people into precariousness

- Dossier

- Apr 23

- 7 mins

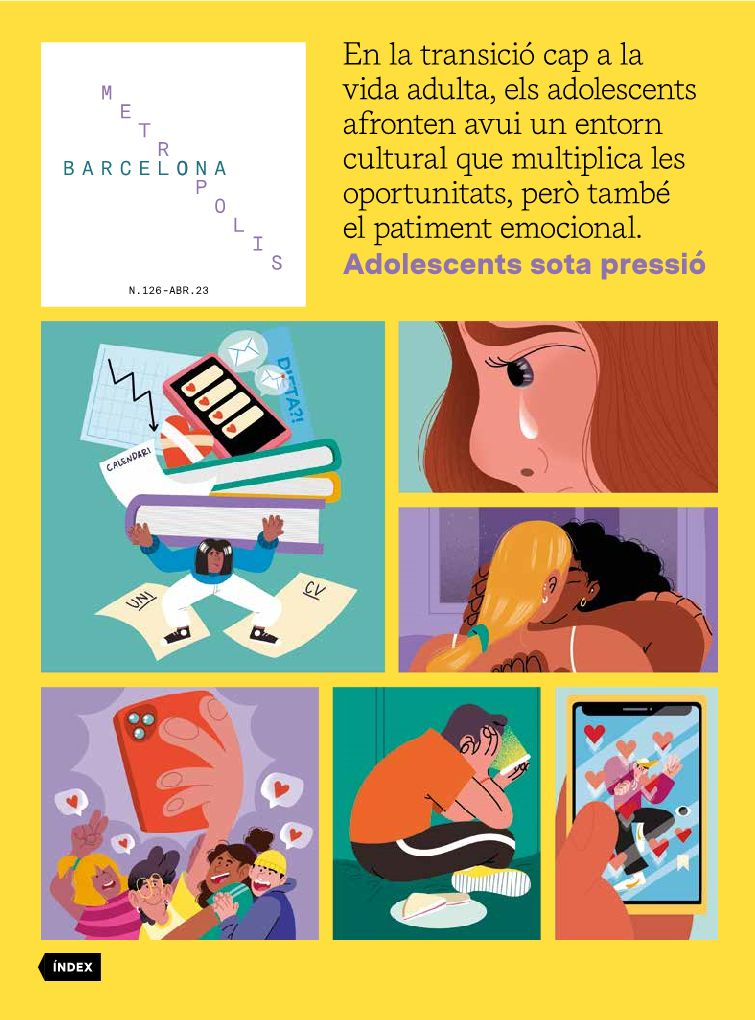

Individualism and competitiveness have encroached on many aspects of young people’s lives. They are exposed to constant comparison with others and the fear of not meeting expectations. While the world of work touts the benefits of entrepreneurship and flexibility, young people and teenagers are also clamouring for the right to a stable life plan.

Young people are facing a real emergency that should set alarm bells ringing. Emancipation rates at all-time lows, worrying levels of temporary and part-time work, youth suicide as the leading cause of unnatural deaths, and the criminalisation and stigma surrounding those who do not conform to the expected norms are just some examples of a long list of factors that put us under pressure. We young people have grown up amidst successive crises that have marked fundamental aspects of our lives and have upset some of our life plans.

It is hardly surprising that these situations affect us so much: the pillars on which our reality is based have been terribly shaky for far too long, and they are getting weaker and weaker. How can we live hanging on the fulfilment or failure of all the expectations that have been created (and continue to be created), and that we internalise as our own?

We young people have been saying for some time now that we don’t want to go on living like this. We don’t want it for the future, neither our own nor that of those to come, but we want it either for the present. We do not wish to keep on perpetuating expectations of a better future if there is no real action to achieve it, and this depends on the real commitment of many political and social agents. Not only do we young people bring issues to the table, but we also offer possible solutions and we intend to be part of the change to put an end to most of the paternalistic and adult-centred discourses. We have adequately shown that we are effective advocates and that we can make a contribution at first hand. We did it again, for example, last May, during the Monographic Plenary Session on Youth in the Parliament of Catalonia: we denounced the highly individualistic and competitive system that has been instilled in our collective imagination, normalising situations that are far removed from the reality that we aspire to.

Individualism and the culture of effort

From an early age we are constantly bombarded with highly individualistic messages and told that the “culture of effort” (and, for some, meritocracy) must be our goal, above all else and everyone else. We grow up thinking that life is a race against our peers, not a shared experience, and that we must apply this approach in many realms of life, from the physical to the mental, from the material to the abstract. We learn to compete in physical appearance, from unhealthy comparison based on models that have led to horrifying data on eating disorders and self-perception, a phenomenon that has been exacerbated in the wake of the pandemic lockdown. We compare our family and social origins, which for some are decisive, and which mark the worth of some, from the point of view of elitism and classism.

The message reaching young people is that, “if we want to, we can”. And if we don’t succeed, it is probably our own fault, because of our lack of effort and willingness to work.

We also grow up comparing our academic performance, as if it were a determining factor in a person’s worth. We compete in terms of future prospects, a long road that we forge individually in most cases. We ultimately grow up with the fear of disappointing ourselves and others by not achieving the goals that are set as our ideals. The message reaching young people is that, “if we want to, we can”. And if we don’t succeed, it is probably our own fault, because of our lack of involvement or our lack of effort and willingness to work. We are promised that the more we study, the better the opportunities and conditions we will enjoy. But we find that we are the first European country in terms of overqualified young people; that is, with more young people performing tasks that fall below their academic qualifications and with working conditions that do not allow them a decent standard of living.

All this leads to many consequences, and this is also reflected in our mental health: we consider psychological suffering to be a private matter, loaded with social stigma, which we must handle individually, trying to go unnoticed. Where have the social support networks gone? How can we learn to support and help our peers when we are not taught to recognise and understand our own emotions either? We need emotional education that provides us with tools, as a community, to be able to learn to deal with the obstacles that we will inevitably encounter in our lives, and which, especially in adolescence and youth, cause so much distress.

Job insecurity and collective struggle

In a talk organised by the National Youth Council of Catalonia in 2022, Magda Casamitjana i Aguilà, director of the Mental Health Board in Catalonia, presented a very alarming fact: in the last fifty years, the number of social points of reference we have has fallen sharply.

Social points of reference are those people, be they family members, friends or colleagues, to whom we can turn in the event of experiencing a situation of emotional distress. In fifty years, we have gone from each person having ten points of reference on average to just one. Just one person to turn to, which shows the extent to which we have internalised and normalised the individualistic discourses that shape this fundamental aspect of our lives.

Individualism and competitiveness have also encroached on our world of work: we are told, in a rather sugar-coated and embellished way, that the best way to approach our professional lives is to become “our own bosses”. The benefits of being self-employed are lauded and we are urged to be entrepreneurial and willing to change jobs often, in a system of the utmost flexibility, both in terms of time and space, so that we can work anytime, anywhere in the world.

The message we get is that this model is to our benefit, so that it is we ourselves who ask for these opportunities in order to be able to adapt better to the way we live: nomadic, not very stable, ever-changing. But they are wrong: we believe that we must indeed revise the current employment model; but to make it more humane and adapt it better to a reality that calls for reconciling different aspects of our lives, not to legitimise the precariousness of young workers. We also desire stability and the possibility of having a life plan, without wrapping temporariness and precariousness, unfortunately so typical of the reality of youth employment, in a romantic mantle of false freedom.

Moreover, history has taught us that it is the collective struggle that can change things, in every domain, and especially in the world of work. By individualising and delocalising our working environment, we only manage to weaken common and collective foundations, such as trade union organisations, which require workers to have direct and constant contact with each other.

We need to revise the way we talk about young people: most of the messages are negative, and the Covid-19 pandemic is a perfect example to illustrate this.

Finally, we need to revise the way we talk about young people: most of the messages are negative, and the Covid-19 pandemic is a perfect example to illustrate this. We young people were the most irresponsible, the least caring and had the most reprehensible behaviour. But the pandemic was a very tough time for us, among other groups, because once again we witnessed how many of the expectations placed on us were dashed in a matter of weeks. Once again, what we were told was that we would be a new generation of young people, victims of the crisis, and that we could put aside many of our plans. And all this while we are labelled the “glass generation” because we are told that “we complain too much from the comfort zone”. Once again, they are wrong: we complain because we have the right and the legitimacy to do so, because we want to change a society that instils its expectations in us and makes us feel bad for not meeting them, blaming us for what they consider to be a failure.

This is the reality we are coming up against. But the message that we, as organised and involved young people, want to convey is that, by working hard and networking, we can start to change it. We face a clear structural and fundamental problem that has been perpetuated for far too long, in highly individualistic and competitive systems, and small, one-off actions alone are not enough to tackle it. To bring about the changes we need, we need real commitments: no one can live on words alone; we need clear actions and commitments. And we want to be a part of this process of change.

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments