The right distance

- The Story

- May 20

- 8 mins

I didn’t mind getting up early to wait for her on the corner with Vinyals and escort her to the underground. It was five, ten minutes, held back at every traffic light and, a few more minutes, at the entrance to the underground. Then I was heading to the gym and she was going to work. María works as an office clerk in a law firm.

In the afternoon, except on Tuesdays and Fridays, I’d wait for her in a coffee shop near her office, we’d rent a room and spend a couple of hours together. María is married with two young children and I’m married with one child, who doesn’t live at home. We met almost by chance, and we soon became lovers. Neither of us feel comfortable cheating. She argues that her children are young and I accept that. Would I like us to live together? I suppose so. I think I could be happy, but sometimes I wonder, although I don’t let it show. It’s clear that the situation has reached a point where it has to go somewhere and maybe I should put pressure on her, but, faced with the quandary, I fear that she’ll choose not to hurt her children. Besides that, admittedly, I’m afraid of having her and indulging in the fantasy. Realising that I’m just a mirror: if I’m loved, I love. If I’m not loved, I fall in love.

A week before the lockdown was agreed, my wife and I were having dinner at home. I brought up the topic of summer holidays. The idea was to travel to Croatia but, given the situation, it was sensible to look for a second option, within Spain:

“They weren’t very expensive. But I think we should cancel them anyway”, said my wife.

“Why…?”

“Because, if I’m honest, I think I do fancy the trip but I don’t know if I fancy going on the trip with you. Sorry to tell you like this. We’ve already talked about it loads of time. We are getting by. Just about.”

I kept quiet. I immediately recognised both the feeling of panic and the desire to be faithful to my wife. Nevertheless, when I opened my mouth my deplorable lack of tact blurted out:

“Are you cheating on me?”

“No, but you are.”

The conversation was left there, hanging in mid air. I didn’t deny it, which was an admission. I could have fought, explained, and pig-headedly and absurdly tried to convince my wife that there was no infidelity, but I didn’t. I accepted the crime, the penalty and the escape tunnel: María.

That night, like every night, I waited for María to send me a text message. She told me about her day, and I told her we should talk. She wanted to know what was going on. I wouldn’t tell her over messages. She said that all the mystery scared her. I tried to reassure her. She called me at lunchtime to say that they were sending her home, that as of the following week everyone would be working remotely, but on account of her asthma attacks, she was a person at risk and they were letting her start remote work early. We met that afternoon, in the usual coffee shop:

“We’re getting a divorce.”

María didn’t say anything. With both hands she cupped her mug of steaming green tea. She brought it to her lips and drank from it. I must admit that I expected another reaction, but I understood her. That’s what my head was telling me, but my ego felt hurt.

“It’s me. It’s got nothing to do with you.”

“Maybe you can still reconcile...”

“María, I’m not going to fight for my marriage. It’s fine. We respect each other and that’s it. Sorry this is bad news for you.”

“Don’t be cynical. The thing is that, whether we like it or not, it puts more pressure on me. Understand me. I only ask that of you.”

“Just the day before the lockdown began I told her that I was sure we could be happy. That it would be hard at first but that everything would fall into place.”

The rest of the week went by as usual. In fact, we were able to see each other for more hours. I was trying not to sound anxious, and I didn’t bring up the subject again. At home we had already decided to get the apartment valued and, from there, see who could keep it on. I didn’t mention any of that to María. I just told her, the day before the lockdown began, that I was sure that she and I could be happy. That it would be hard at first but that everything would fall into place and what we no longer had, sharing a life with someone you love and desire, would be within our reach. She kissed me automatically, without warning.

“You’re the most important person in my life”, she said, and I believed her.

As of the next day, the lockdown already had to be strict. At home, the decision over our cohabitation was contingent on when this disaster passed and, without having to say a word to each other, we lived apart. She slept in the bedroom and I slept on the dining room sofa. We did eat together, did zoom video calls with our son together and watched the news just as stunned and bewildered as one another.

As of María, our relationship via mobile phone stepped up a notch. Her circumstances for our relationship were worse, since their apartment was half the size of mine and they were twice the number of people. That’s why we agreed to go to the only supermarket in Plaza Catalana and meet there every two or three days. Sometimes we’d happen to meet in the queue to go in, one metre apart, and other times inside, wasting time between the meat trays or picking oranges or apples, whatever nonsense, like two teenagers. We loved seeing each other. We brushed our gloves up against one another’s when no one was looking at us and under the facemasks we said how much we missed one another. We discussed the news over all the madness and we wondered when it’d come to an end. I knew that she was in a risk group, and I was concerned about her condition. I even scolded her for being the one to go out shopping.

“I go out to see you.”

“Someday all you’ll have to do is come home to see me.”

“We have always been different this way. Me, clinging to live in the present without thinking about the future and you, ensconced in the future as if the present were a nuisance.”

“Maybe. The present is running out. Or maybe it’s easier. I love you. I want to be with you. I want to feel that I am where I should be.”

“I love you too.”

“But one day, when I went to the supermarket on time, she didn’t show up. I wrote to her, but she didn’t reply.”

Over the following days our communication carried on as usual. But one day, when I went to the supermarket on time, she didn’t show up. I wrote to her, but she didn’t reply. I did so all day. I called her, but nobody answered the phone. I started to worry. I wrote her an email. Nothing. I finally established that she had blocked me on her phone. Two days later, I went to the supermarket and confirmed that it was her husband who was doing the shopping. We didn’t know each other, so I couldn’t strike up a conversation about her.

All my subsequent attempts were futile. I wandered around her apartment block in case she leaned out of one of the windows; I wrote to her anyway by any means within my grasp, without taking any precautions, in case the email was opened by someone other than for whom it was intended, or her Twitter account. The only logical explanation was that she had fallen ill. And that she had done so in such a way that, given her asthma, things had worsened. Perhaps she had been admitted to those chaotic ICUs, alone in a hallway, or struggling between life and death. It was absolute torture for me. If she died, I’d never know, or at least not until all this madness had passed and I could find out at the law firm where she worked. Still, I tried to relax. I tried – with no luck – not to check anything on her social networks on my mobile. But despite all this, the anguish of not seeing her anymore, that she was perhaps alone and dying, or already dead, wouldn’t let me sleep or live. I stopped walking around her apartment block and going to our supermarket. I went shopping in one closer to home. And there I saw her again. She was in the middle of the queue to pay, distracted, typing something on her phone. After the first few seconds of surprise, I headed towards her, not quite knowing what to say, whether to scold her for her behaviour, or perhaps waiting for an excuse that, however poor it was, I’d like to accept. I was a couple of metres away from María when someone behind me reminded me, ill-manneredly, that I should go to the end of the queue and respect, as I wasn’t doing so at the time, the proper distance. I called out to her, but she didn’t turn around. She stopped typing on her phone, looked up, and fixed her gaze on the back of the neck of the guy who, one metre in front of her, was about to put his shopping on the conveyor belt at the checkout.

Recommended publications

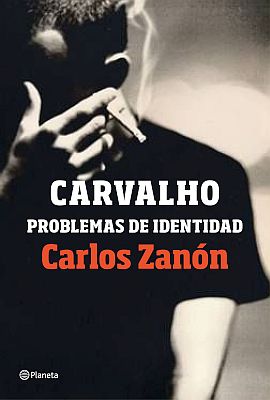

Problemas de identidadPlaneta, 2019

Problemas de identidadPlaneta, 2019 Salamandra, 2017

Salamandra, 2017

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments