©Albert Armengol

The manufacturing laboratory for the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia.

This September we commemorate the tercentenary of the end of the War of the Spanish Succession. During the long months of the siege of Barcelona, the city displayed remarkable self-sufficiency and civic organisation in its resistance. Three hundred years later, that heroic Barcelona, which had enough self-confidence to concede and save itself from destruction, is an open city that has surpassed all manner of physical and psychological barriers. As a city that has suffered sieges and bombardments throughout history, it does not base its strength on trying to defeat external forces or relying on them, but on its ability to generate its own resources. Indeed, if, as the saying goes, every country makes its own war, then every city makes its own market. Nevertheless, and despite its status as an open city, Barcelona is living, paradoxically, under the pressure of a new siege.

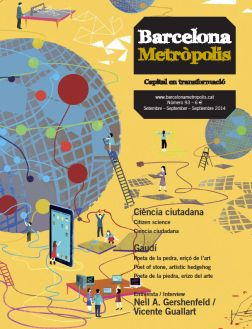

This is not a military siege, but an economic one: under the banner of globalisation, its industry has been dismantled and production has shifted to developing countries. As MIT professor Neil Gershenfeld said in an interview for this issue of Barcelona Metròpolis, the factory production model of the 19th and 20th centuries has given way to a service economy and led to a situation where products are imported and jobs exported. Our current crisis is largely a result of this economic siege.

The notion of an economic siege takes us back to the paradigm of the self-sufficient city, as described so well by Vicente Guallart, chief architect at the Barcelona City Council and promoter of fab labs and digital manufacturing associations. “The challenge for cities in the 21st century is becoming productive again,” says Guallart. “Now, more than ever, our self-sufficiency needs to be connected, global.” Replace self-sufficiency with sovereignty, and you get a sentence with a viable political solution for the city and the country. “The challenge, then, is to move from the model of a city that receives products and generates waste to a different model in which information comes in and goes out. An innovative city is one that allows its citizens to think globally and produce locally,” affirms Gershenfeld.

Hence, Barcelona is not immune to global sieges. Like all big cities in the world, it must be prepared for threats such as climate change, which may bring a multitude of natural disasters, and terrorism. It is not enough for a city to be highly self-sufficient if it doesn’t belong to a network that enables it to establish universal protocols. After all, connected self-sufficiency offers greater protection against global collapse. Nor is it a coincidence that Barcelona has become the world capital of urban resilience, one of the foundations that must allow the smart cities of the future to enjoy greater energy self-sufficiency and be in a position to cope with energy blackouts caused by accidents or sabotage.

However, a smart city is not just a city with sensors. Being a mobile capital and having protocols to make it a smart city will be useless without science and public innovation. It is not enough to create apps that merely integrate people into the smart cities of the future. We also need a public that is open and ready to participate, and above all prepared to share in innovation.

No wall will help us deal with these threats. It is not, therefore, a question of building new barriers, but quite the opposite. Only through imagination and public cooperation will we be capable of overcoming the sieges of the future.