Participation is vital for structuring the transformation of the city. And the educating city is the basis of all new forms of participation.

We are approaching the end of a memorable year, a politically intense one in which the power of citizen participation has left an indelible mark. Now is a time to reflect on what we know and feel: this year – when we commemorate the tercentenary of the events of 1714, one of the most painful episodes in the history of Barcelona – we have lived through one of the most dynamic, decisive and hopeful years of our time.

2014 was a year distinguished by the expression of collective will. The avenues of Barcelona were the scene of one of the most massive demonstrations in the history of Europe: hundreds of thousands of Catalans coloured the city’s streets in an unprecedented calligraphy for the sole purpose of expressing a shared longing. All of this leaves us with the lesson that cohesion requires collaboration.

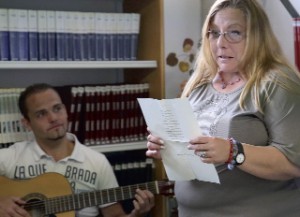

Just as municipal policies derive from a mandate decided at the polls, a political agenda can only be implemented effectively with the public participating as active stakeholders. Conversely, only when the associative capacity of Barcelonians has been expressed through intelligible aspirations has it been possible to shift these into the political realm. As Isona Passola says in her interview in the opening pages of this edition of Barcelona Metròpolis: “People speak ill of politics, but they would do well to remember that if you do not do politics, others will do it for you.”

Hence, once again, cohesion requires collaboration. When collaboration is present, cohesion is the reward. The concept of collaboration has been one of the guiding principles behind Barcelona Metròpolis magazine over the past two years. Within the new digital paradigm in which we are now immersed, citizen participation plays an essential role in structuring urban transformation. This assertion holds true irrespective of whether we are talking about smart cities, urban resilience, citizen science or the new knowledge economy, and at the foundation of all these new forms of participation is the educating city.

This issue’s monograph focuses on the Congress of Educating Cities, held in Barcelona this past autumn, an event that brought together representatives from more than 470 cities around the world. An educating city is one that provides and ensures the education of its citizens beyond the confines of schools, universities and other conventional teaching environments. The educating city creates places for sharing knowledge and disseminating it to the public: libraries, athenaeums, neighbourhood associations, community centres, art factories, citizen laboratories and – why not? – also prisons. Such cities are porous, acting and innovating with an inclination for inclusion. They seek innovative formulas for participation and incorporate innovation at all levels of participation. From a triangle formed by inclusion, participation and innovation, the educating city creates a virtuous circle.

The educating city is not an institution operating over and above the citizenry. Rather, it embodies the capacity of people to weave the very fabric of citizenry. While Barcelona is a city designed from successive planning initiatives, it has been most successful when its transformations were the product of cooperation amongst its people. It is from this same source that dissent has arisen; those critical voices offering nuances to official discourse and enriching the city’s narrative. The job of those who govern is to listen astutely to citizens who warn against actions of exclusion and remind us that real advancement does not take place when the citizenry is left behind. Ultimately, an educating city is one that embraces the right of citizens to formulate their own political mandate.