'Cròniques del fang'. When journalists wandered the streets

- Books

- Culture Folder

- Oct 22

- 7 mins

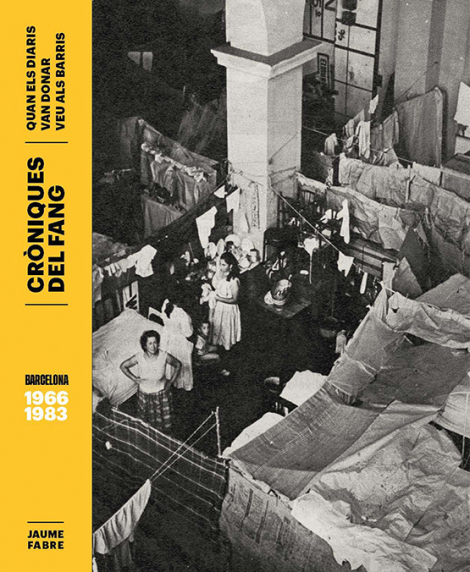

Through the book Cròniques del fang [Mud Chronicles], Jaume Fabre pays a fitting tribute to the journalist Josep Maria Huertas Claveria and the journalism named after Huertas. The book’s author also endeavours to understand the city and the profession beyond the figure of Huertas.

In spring 2013, at the Association of Catalan Journalists, the president of the Federation of Neighbourhood Associations of Barcelona (FAVB), Lluís Rabell, presented an anthology of reports published by the magazine Carrer entitled Josep M. Huertas Claveria i els barris de Barcelona [Josep M. Huertas Claveria and the Neighbourhoods of Barcelona]. Rabell drew an analogy between the journalist Huertas Claveria (1939-2007) and the trade unionist and member of the French Resistance André Calvès (1920-1996), who entitled his memoirs Sense botes ni medalles [With No Boots or Medals]. The same anthology was used a few days later – at the unveiling of the plaque that named a square in Poblenou after the journalist – to commemorate that Huertas was a straightforward, generous and hard-working person. So much so that he entitled his memoirs Cada taula, un Vietnam [Every Table, A Vietnam] and defined the history of journalism during the transition as El plat de llenties [The Plate of Lentils].

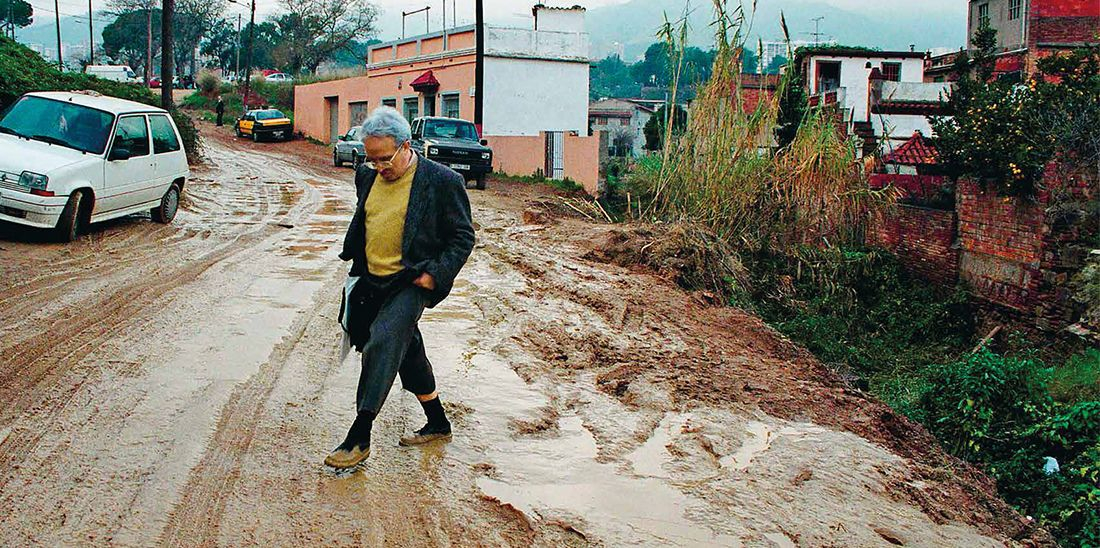

He probably wouldn’t have wanted plaques or medals, but rather boots. Because Huertas used to complain about sore feet and wore out heaps of shoes, from all his traipsing around the neighbourhoods, engaging in journalism that should be advocated; even graphically, like a photograph of Pepe Encinas on the title page of Cròniques del fang. Quan els diaris van donar veu als barris, by journalist and historian Jaume Fabre (Barcelona, 1948).

José Martí Gómez used to refer to the need “to get one’s shoes dirty” to describe the act of wandering the neighbourhoods and the streets, the only way to acquire social sensibilities, to satisfy one’s curiosity for information and to activate the journalistic sense of smell necessary to properly undertake the “the most beautiful profession in the world”. And this includes, as the neighbourhood activist Andrés Naya recalls in the foreword to Cròniques del fang – quoting an article by Fabre in Tele/eXprés –, that the metaphor of dirty-shoe journalism could become a reality in a headline: “II Cinturón: Barro para años” [The Ring Road: Mud for Years].

Tribute to Huertas and to huertamaros

This mud is the subject of a work that, as the author says, is lots of things all at once. It is a tribute to Huertas “and to all those that, like him, engaged in social journalism” at the end of the Franco regime and during the transition to democracy, with the involvement of the neighbourhood movement. In fact, besides Naya, Fabre is accompanied by a fine list of huertamaros like him: Juanjo Caballero, Jordi Capdevila, Pepe Encinas, Maria Favà, María Eugenia Ibáñez, Manel López, Eugeni Madueño, Amparo Moreno and Antoni Ribas. All of them combined – featuring an original structure, attractive photos and reproductions of newspaper archives, and painstaking graphics editing that recalls a newspaper layout – are the chronicle of a time, a country, a city and local journalism worthy of being studied in depth.

Journalist Tonia Etxarri (in the foreground, on the right) covering a demonstration for Tele/eXpres in the neighbourhood of La Trinitat, in May 1977. © Pepe Encinas

Journalist Tonia Etxarri (in the foreground, on the right) covering a demonstration for Tele/eXpres in the neighbourhood of La Trinitat, in May 1977. © Pepe Encinas A group of journalists interview Juan José Moreno Cuenca, El Vaquilla, who appears in the window of Barcelona’s Model prison on 13 April 1984. The famous criminal was leading a riot with hostages. © Pepe Encinas

A group of journalists interview Juan José Moreno Cuenca, El Vaquilla, who appears in the window of Barcelona’s Model prison on 13 April 1984. The famous criminal was leading a riot with hostages. © Pepe EncinasThe book is a tribute to Huertas and to all those that, like him, engaged in social journalism at the end of the Franco regime and during the transition to democracy, with the involvement of the neighbourhood movement.

In Periodistes, malgrat tot. La dificultat d’informar sota el franquisme a Barcelona [Journalists In Spite of Everything. The Difficulty of Reporting During the Franco Regime in Barcelona] (2017), Fabre had already tackled the period 1939-1966 with the rigour of a historian with a cum laude thesis, published in 2003 under the title Els que es van quedar. 1939: Barcelona, ciutat ocupada [Those Who Stayed. 1939: Barcelona, Occupied City]. Applying the same historical rigour, but with an interesting added reflection on memory, he now focuses on a period that he himself lived through as a journalist. It is the period between Manual Fraga’s Press Law and the official opening of the Museu Picasso by José María de Porcioles, in 1966, and the beginning of Pasqual Maragall’s mandate and the inauguration of Joan Miró’s sculpture Dona i ocell, in 1983, the same year that Barcelona’s newspapers saw the arrival of the first computers.

El Periódico, Avui, Mundo Diario, Tele/eXprés, El Correo Catalán, El Noticiero Universal, Diario de Barcelona, La Vanguardia, Catalunya Exprés, Solidaridad Nacional, La Prensa and Hoja del Lunes, alongside magazines such as 4 Cantons, Grama and El Maresme, are the main press that comprise the book and have their own section. This is accompanied by a long list of journalists, with snippets on their professional origins, anecdotes and interesting photos, pseudonyms and political affiliation. Around 700 names that are easy to find thanks to an index of proper names and, besides the omnipresent Huertas, Lluís Bassets, Manuel Campo Vidal, Pere Oriol Costa, Gonçal (not Jordi) Évole, Maria Favà, Rafael Pradas, María Eugenia Ibáñez, José Martí Gómez, Jaume Perich and Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, have their own appendix.

From neighbourhood struggles to the deception of memory

Cròniques del fang is not, however, the umpteenth history of Barcelona; nor the nostalgic portrayal of print journalism; nor the biography of Huertas that one day will have to be produced; nor the chronicles of huertamaros, a gentilic hitherto attributed to Joan de Sagarra and whose true origin is revealed by Fabre, in 1971: Joan Garcia Grau, manager of Oriflama and linked to José Mujica’s Tupamaros [Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group in Uruguay in the 1960s and 1970s]. Nor is Cròniques del fang a compilation of the battles of the neighbourhood movement that, in 2022, celebrates the 50th anniversary of the FAVB.

The book has a little of all this. Because, as Fabre says, “it is a story of a time of awakening of both journalism and the community struggle, when the country was beginning to emerge from the tunnel of Francoism”. It is essentially about neighbourhood reporting. And this “includes the style of reporting on all kinds of popular and labour demands taken up by neighbourhood associations, from the demands for services and facilities to the demand for urban planning on a human scale, housing problems, the defence of the Catalan language and heritage, the recovery of historical memory, support for companies on strike, the fight for freedom of expression, and the denunciation of municipal corruption and speculators”.

As Jaume Fabre asserts, this book “is a story of a time of awakening of both journalism and the community struggle, when the country was beginning to emerge from the tunnel of Francoism”.

The book, a must-have on the shelves of faculties and publishing offices, is also useful to reflect on the deception of memory. “The act of remembering is made up of memories, while history is based on sources”, a quote by Pierre Nora also included by the historian Enzo Traverso in his essay Passats singulars [Singular Pasts] (2021). In this vein, based on specific examples and thanks to the author’s dual status as historian and journalist, Cròniques del fang warns us against another kind of mud, that of fake news. According to Fabre, the conclusion: “One of the basic principles for good historians should also apply to journalists, despite the haste with which they are forced to work: any information must always be checked against various oral, documentary and bibliographic sources”.

Head of the historic demonstration of 11 September 1977. Politicians and photographers of the time, face to face. © Pepe Encinas

Head of the historic demonstration of 11 September 1977. Politicians and photographers of the time, face to face. © Pepe EncinasThis ground rule is applied Cròniques del fang, and it shows. But the most fundamental one stands out: wandering the streets. And this brings us back to the initial analogy and the foreword of Sense botes ni medalles, in which Calvès explains that the publisher decided the title because it was more commercial. The French trade unionist preferred another, which he used in a reprint: J’ai essayé de comprendre. I tried to understand. Trying to understand the world, the city where we live, wandering the neighbourhoods and the streets, which is precisely what Huertas did. His friend Fabre also tries to understand (and to make us understand) a city and a profession, a time and a country that is still ours through a book that is the distinction deserved by Huertas and the journalism to which he lent his name while giving neighbourhoods a voice.

Cròniques del fang. Quan els diaris van donar veu als barris. Barcelona (1966-1983) [Mud Chronicles. When Newspapers Gave Neighbourhoods a Voice. Barcelona (1966-1983)].

Jaume Fabre

Barcelona City Council, 2022

325 pages

The newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up to date with Barcelona Metròpolis' new developments